|

When it comes to forest policy, the public sphere is often filled with demands that our wilderness areas need absolute protection from human encroachment.

In Southern Oregon, we see these same demands flourish with claims that expanding the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument would preserve biodiversity and protect these forests for generations to come.

The problem with this narrative is that current evidence runs contrary to this Utopian hope.

How can I say that? Let’s play a thought experiment with our forests.

We’ll let the “protect the wilderness” experimenters loose on a million acres of Oregon forest. During the first year, there would be hikers, campers and just everyday folks enjoying the great outdoors.

After a couple of years, the wilderness would become extremely difficult to navigate without roads built and maintained by loggers. In subsequent years only the hardiest would bother to take the kids camping because of the danger and difficulty in navigating the wildlands of an overgrown and brushy forest.

Fuel loads grow

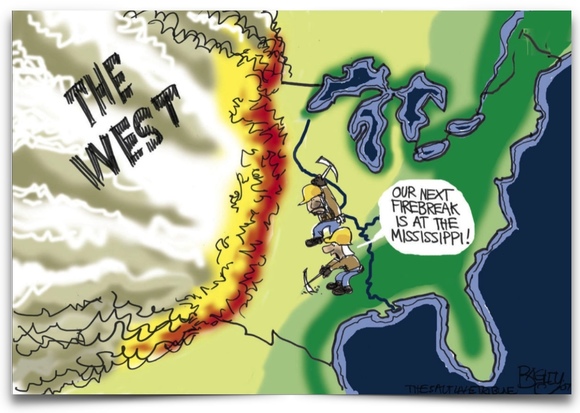

Without any human intervention, thinning efforts or grazing permits allowed, the fuel loads would build until lightning storms cause a mega-fire that is typical for unmanaged wilderness. The wilderness designation would dictate that lightning caused fires would be permitted to play out, as nearly as possible, their ecological role within a wilderness area. Meaning, “let it burn.”

So, after several years, the remaining forests would be marginal at best; wildlife habitat would be destroyed; streams and watersheds would be polluted with ash, dirt and debris; and downstream fish habitat would be fouled.

Tourism would see significant declines as people naturally avoid vacationing in smoke-filled Oregon. The carbon emissions from these mega-fires would harm our human populations and healthcare costs for particulate matter inhalation would be significant.

Now, let’s take a

million acres and manage it for sustainable yield logging and maintain

it in a way that would not only supply lumber, but also recreation,

benefiting the public with areas for camping, hunting, hiking, picking

berries, winter snow sports, and just enjoying the accessible

wilderness.

Until

the early 1970’s forests were managed by the loggers. They would harvest trees,

thin forests, allow grazing, re-plant and keep wildfires contained because this

was their livelihood. They would cut

access roads and the public would gain by this accessibility.

Repeating

this policy would sustain the forest for generations, giving the newly planted

trees time to grow into usable timber. Our summer air would be breathable again

and we would be able to enjoy the natural beauty of our state. Tourism and

prosperity would increase as folks would be confident that their vacation would

not be shadowed by smoke.

Benefits worthwhile

Additionally, as byproducts of sustainable-yield forestry, there would be high employment in forestry operations, milling, freight hauling, home construction, heavy equipment, and thousands of other subsequent opportunities. This would generate tertiary benefits through the direct creation of wealth from the astute utilization of our natural resources. Additionally, reducing the size and scope of mega-fire incidents leads directly to increased

CO2 sequestration because healthy forests absorb vast quantities of CO2.

Now, my forest scenario might have its own Utopian twist but, today,

we see the dire results from the “protect the wilderness” experimenters via improper and unrealistic

forest practices.

Our communities pick up the tab and suffer the consequences of this “let it burn” policy through the destruction of assets, loss of watersheds and wildlife habitat, loss of recreational opportunity and degraded forest resources.

The benefits in my scenario come from the same land that the “protect the wilderness” experimenters used. The difference is in policy – policy aimed at the

sagacious utilization

of our natural resources that would generate benefits for the land, wildlife, our watersheds and all Americans.

Unfortunately, we are living amid policies dictated by the “protect the wilderness” experimenters and it is not pretty.

Fires get worse

Up until the 1980s, the average duration of wildfires was just six days. The number of distinct fires or ignitions hasn’t changed over time but wildfires, today, are much larger and last much longer. Today, the average fire lasts 52 days, or nearly two months. The Chetco Bar fire is estimated to double the 52-day average, with nearly four months of burn.

Last winter was a record-setting winter for cold, snow and rain. The drought is over; our reservoirs and dams are full; rivers and streams are still flowing with snowmelt. Could it be that these extraordinary burn rates are directly related to policy and not to global warming?

The overall solution is not complicated — in fact it’s simple. Let’s allow balanced human wisdom, ingenuity, and expertise a voice at the table to bring common sense and local control back to our forest management.

Or, better yet, let’s throw this failed policy into the fire.

Remember, if we don't stand for rural Oregon values and common-sense – No one will!

Dennis Linthicum

Oregon State Senate 28

Capitol Phone: 503-986-1728

Capitol Address: 900 Court St. NE, S-305, Salem, Oregon 97301

Email: sen.DennisLinthicum@oregonlegislature.gov

Website: http://www.oregonlegislature.gov/linthicum

|